SCULPTURES

Lalitankura Pallava Griham, A neglected Pallava treasure on Tiruchirappalli Rockfort

by Prof. Subramanian Swaminathan

e-mail: sswami99@gmail.com

e-mail: sswami99@gmail.com

6 April 2025

There are two iconographic compositions which owe considerably to the

Pallava-s: the Somaskanda and the Gangadhara. Perhaps the former is a

special Pallava conception. Both these have captivated artists through

the ages.

The earliest, (or is it one among the earliest?), is Mahendra Pallava’s

Gangadhara in the cave temple in the Rockfort complex at

Tiruchirappalli. The popular shrines of Tayumanavar and of the Uchchi-

p-pillaiyar are much fancied by the devout and only an occasional art-

buff enters the precincts of the cave temple that houses this Siva

composition. Then there are pilgrims who rest their tired limbs on their

way back from the strenuous climb atop, and the noisy hangers on who

crowd every place of religious or cultural fame. The cave temple

deserves better.

It is not the cave temple alone that deserves better. There are at least

two more ancient sites that should have been in the itinerary of the

public. One is an ancient site, older to the Pallava cave by about 500

years. It is a cavern, a holy resort of Jain ascetics. To attest this,

we have stone- beds where the holy men practised severe austerities and a

number of inscriptions, the earliest being in Late Tamil Brahmi of the

3rd century AD. Unfortunately this is lost, again due to our negligence.

Three inscriptions in Early Vattezhuttu have been found and these are

dated to the 5th century AD. All these mention the name of the patrons

of the Jaina ascetics.

At a lower level is another cave temple. This was excavated by the

Pandya-s perhaps a century later to the Pallava one above. A family

lives in the precincts, unhelpful enough to drive away straying

visitors. I suggest that the Trichy-wallahs pay a visit to this temple

also, as this is believed to have been designed following the Hindu

Shanmatha doctrine of Adi Sankara. (I wish some God-person attributes

some divine powers to the gods hiding in these caves. Perhaps this is

the only way today to make people ‘honour’ these divinities!)

Importance of the Temple

First let me state in brief why the Pallava cave temple is important.

Firstly, it is one among the earliest cave temples of the Tamil country.

It is believed that the Pallava-s introduced excavating hard rock in

the south. May be the Pandya-s were doing this around the same time. At

least Mahendra Pallavan boasts so in his Mandagappattu cave shrine. The

Tiruchy cave is the southern most cave of the Pallava-s. How come he

came all the way to Tiruchy to excavate a cave temple in an inaccessible

hill, we don’t know. Was it under his rule at that time, I am not sure.

But here we have one which is important in the art and religious

history of India. We must try to imagine how this hill would have looked

with out the Tayumanavar Koil, Uchichi-p-pillaiyar Koil and all the

sundry shrines, and then we may wonder how Mahendra chose the site at a

height of 200 feet and how his artisans managed the excavation. Like the

other Pallava monuments this cave temple also holds some puzzles.

The Temple

The cave temple, a typical early Pallava style, is dedicated to Siva.

Mahendra calls the shrine Lalitankura-pallavesvara-griham. Lalitankura

is one among the many titles of Mahendra, and it means ‘charming-

scion’. This name is found on the girder connecting the two inner

pillars of the cave temple. The sculptural content includes two Pallava

dvara- pala-s guarding the now-empty garbha-griham and the famous

Gangadhara panel in bold relief. This panel is an exquisite composition.

It is a pity that all of us miss it. I shall be discussing about it in greater detail alter.

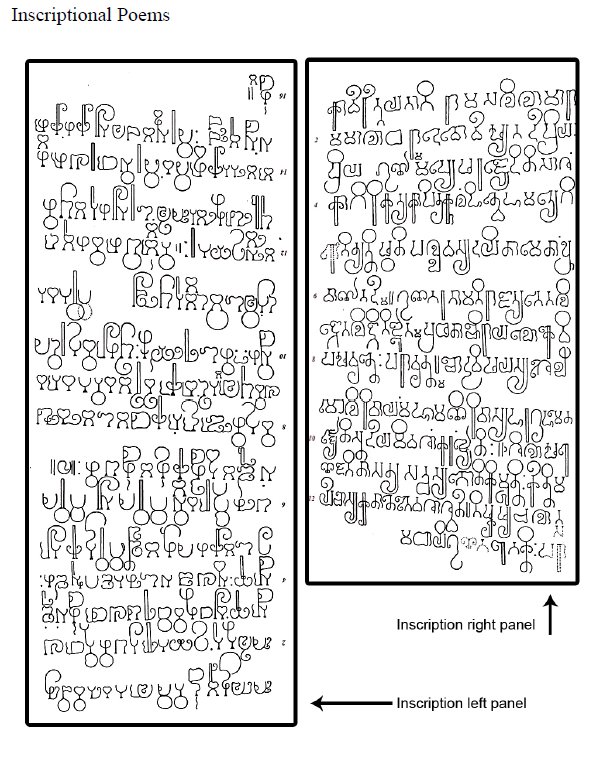

Inscriptions

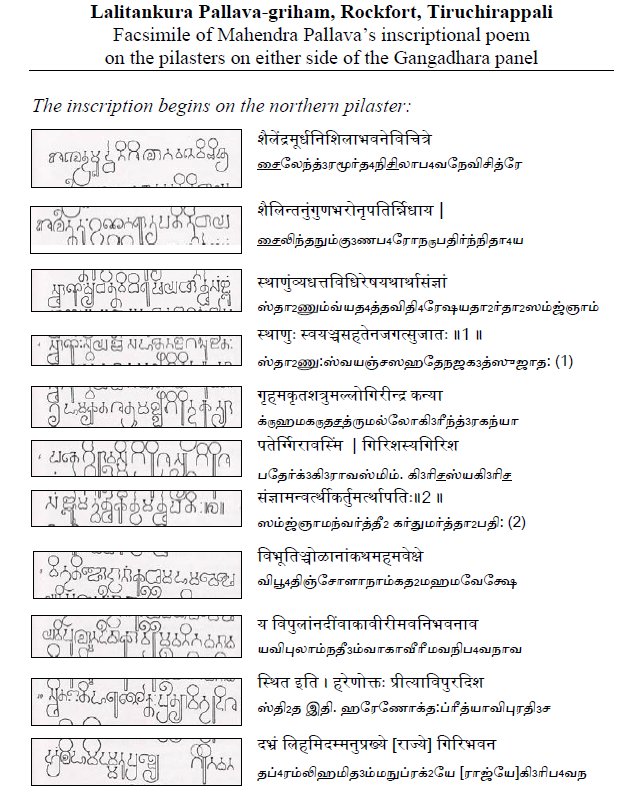

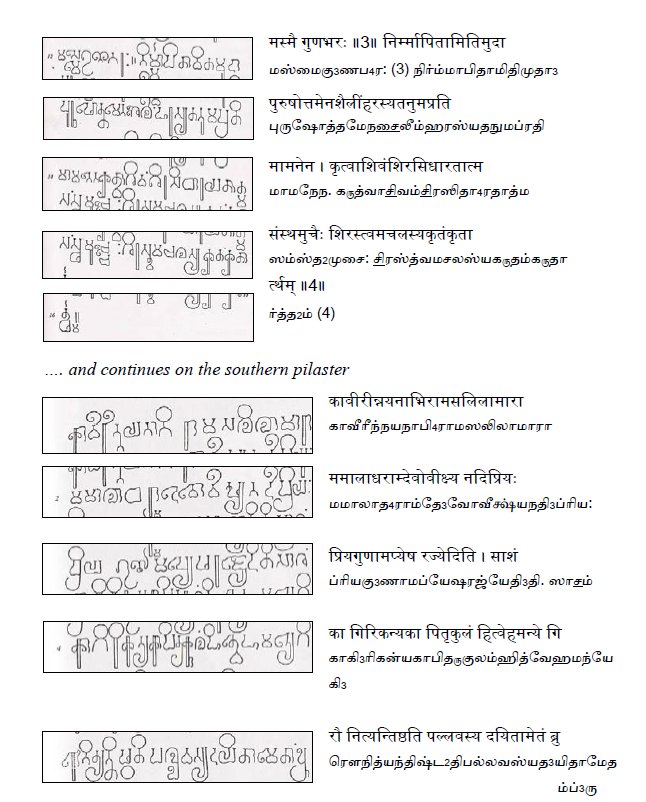

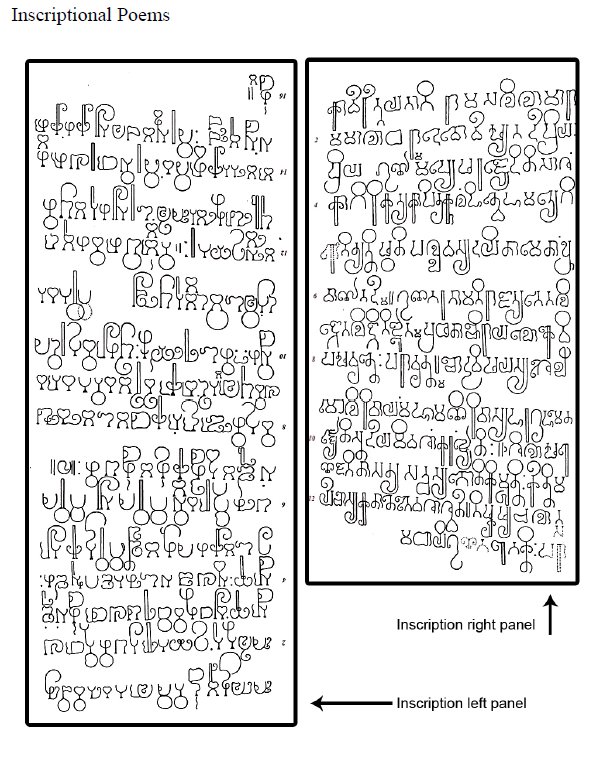

Transliteration and translation of Mahendra Pallava’s inscriptional poem on the pilasters on either side of Gangadhara panel

That the cave contains some important inscriptions is another special

feature. Some of them are the routine listing of the innumerable titles

(biruda-s) of Mahendra Pallava, a decease that infects our rulers of the

past and the present. There are 80 of them engraved in this shrine,

mostly on the pillars. (Mahendra can boast of almost 130 titles! His

great-grand son, Rajasimha, had even more, about 250!) But a poem

consisting of eight couplets, most likely composed by the king himself,

not only describes the Gangadhra panel that it encloses, but also

presents a puzzle, an example of dhvani normally met with in Sanskrit

poetry, here for the first time in a sculpture, to be handled again by

his son in the Great Penance panel in Mahabalipuram.

Pallava Grantha script

I may take this opportunity to mention some thing about the script in

which the inscriptions are written. The language of the couplets is

Sanskrit, and they are written in the script called Grantha, or more

appropriately, Pallava Grantha, giving credit to the inventors. It is a

script used in the Tamil country to write Sanskrit. It was so till the

last generation. It is also the one from which developed the script for

Malayalam, and, hold your breadth, script for most all the languages of

the East: Java, Sumatra, Borneo, Thai, Laos, Khmer, Combodia, Vietnam

etc. This happened through the political and cultural conquest of the

East by the Indian rulers, starting with the Pallava-s.

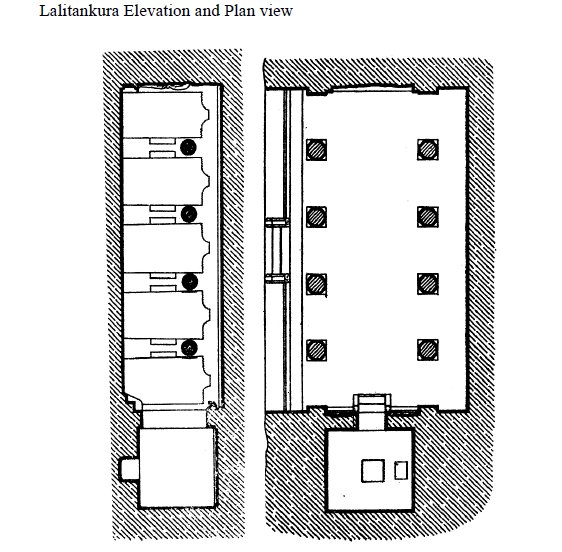

General description of the Temple

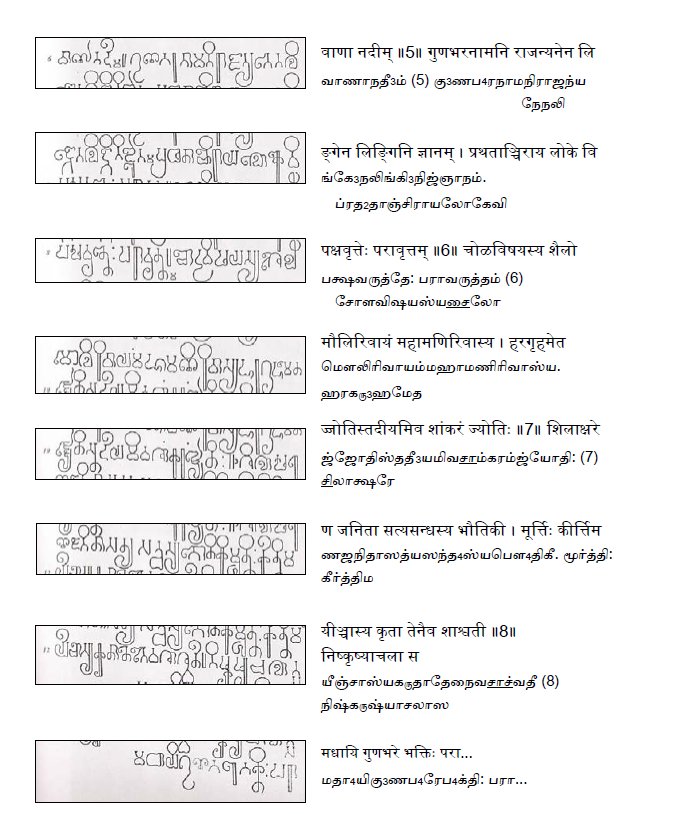

To start with I will give a general description of the cave temple. When

you cross the gate that takes you to the Uchchi-p-pillaiyar temple, you

find on the left the cave temple, called by a mouthful name,

Lalitangura Pallavesvar Griham. What you see is a cave supported by

four pillars with two half pillars

(technically called pilasters) on each end. The façade looks rather

simple. The pillars are plain, square in cross section at the bottom and

top, but eight-sided in the middle. This is typical of early Pallava-s.

The pillars become more and more sophisticated, and to some extant the

design of the pillars gives clue to the chronology of the caves

themselves. There are circular low-reliefs on all the four sides of the

pillars. They are beautiful geometrical shapes, worth a close look. The

brackets above the pillars are again plain. Titles of King Mahendra are

inscribed on the faces of these pillars, mostly in Pallava Grantha and a

few in the Tamil script.

Beyond the pillars is a mandapa (hall), and in the rear the hall is a

series of four pillars very similar to the ones in the front. The

medallions on the faces of these pillars are again worth a few minutes.

To your right, that is, on the eastern wall of the cave, is the

garbha-griham (sanctum).

Garbha-griham

Many of the features of the garbha-griham proclaim its Pallava origin.

First let us look at the dvaral-pala-s (gate-keepers) that guard the

shrine. One on each side, they are carved in bold-relief. They are

similar in certain respects. Both are in semi-profile, two-armed turned

towards the shrine-entrance, standing with one leg bent and raised up

and the other planted firmly on the ground, carry a massive club, their

palms resting on it, etc. When you find time you may look at the

sacred-thread they are wearing, their dress and ornaments. These would

reflect the contemporary fashion.

The garbha-griham is almost a cube of about 9-foot each side. There are

two pits, one, we can guess, is for the lingam to be installed. But what

about the other? Was lingam the object of worship in the Pallava cave

temples is the question that is being debated by pundits. I shall also

be touching upon this later.

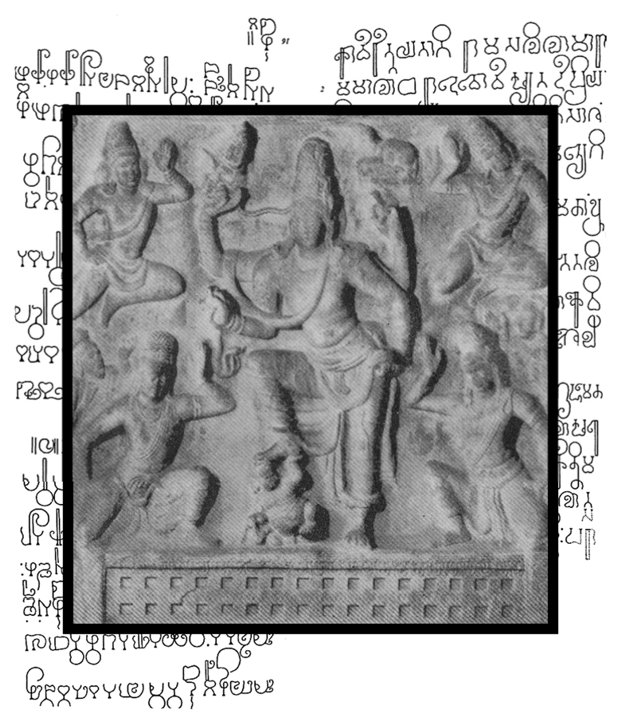

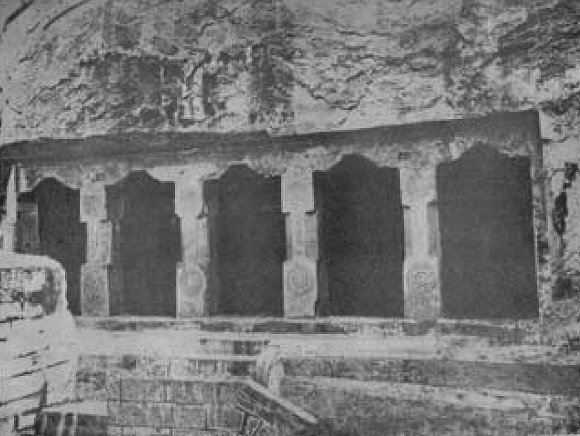

Gangadhara Relief Sculpture

Now let us look at the western wall, the main object of our study.

Here is the celebrated Gangadhara panel. This is a large

composition. In the center is Siva as Gangadhara with attendant figures

on the sides and top.

Let us start with the hero. The four-armed Siva is standing with His

left leg planted firmly planted on the ground. His right foot is raised

and is held up by the head and an arm of a crouching Siva-gaNa below.

Siva’s upper right arm holds a strand of His tresses into which Ganga is

descending. Ganga is shown in the human form, a small female figure

with both the hands in the ‘namaste’ posture.

The lower right hand of Siva holds the tail of a serpent with its hood

raised up. His upper left holds an akshara-maala and the lower one rests

on His hip. These are conventional postures. Now let us look at the

make up. His sacred-thread is vastra-yajnopaveeta, namely, made of

cloth. The ornaments can be listed: coiled valaya-s around the wrists,

elaborate keyoora-s above His elbows, makara-kunDala-s on both ears,

large enough to rest on His shoulders, a broad necklace, an udara-

bandha round His belly.

Siva’s head-dress is an elaborate jaTaa-makuTa, a rather unusual one. It

is decorated on the front and held in position by a coronet. Rest of

the jaTaa is coiled on the top. On the top right side is the

characteristic moon and at the bottom, but on the left side is a skull.

Behind the head is the siraschakra.

Let us look at the dress. His veshTi, reaching up to both the ankles

with the central fan-like pleat of the kachcha hanging between legs, is

worn the way it is done even today, a example of continuity in

tradition. But the artists have done this excellently, every fold, clear

and crisp. Round His waist He wears a kaTi-bandha. Another uttareeya

hangs loose in a loop in front and has tassels on either side. Isn’t

this a remarkable composition?

Now let us follow the other actors in this scene. I have mentioned the

gaNa whose head and palm are supporting the right leg of the Lord. The

crouching gaNa, identified with Kumbhodara, holds a serpent on his right

hand. On the other side, corresponding to the descending Ganga is found

an animal, not easily distinguishable. Because of the prominent hump it

could be a bull. Is it taking the place of vRshabha-dhvaja?

On either side on the top are two flying vidya-dhara-s. Below, kneeling

on either side of Siva, are two identical figures. All these four

figures are attired very similar to the Lord, with the lower pair being

somewhat less ornamented. Their one arm raised in adoration and the

other on the hip. Who could these people, in the royal dress in Siva’s

camp? They look out of place in the Shambo-ki-baraat! We shall come back

to this later. Behind the two kneeling figures are two identical

rishis, identified by their huge jaTa-s and bearded face. Their inner

hands too are raised in veneration.

Now let us take a few steps backwards so that we can get a full picture

of the panel in order to appreciate the beauty of the composition. This

bas-relief is an outstanding composition. It is also the earliest

composition in the Tamil country. That the artist could achieve

aesthetic excellence on their very first attempt is astounding. This

must have inspired his illustrious son, Narasimha Varma, to attempt the

world’s first open-air bas-relief in Mahabalipuram. I may mention that

Mamalla’s unique contributions to the world of art are two: the

monoliths and open-air reliefs. The former had inspired quite a few,

including the incomparable Kailasanatha Temple in Ellora, but none

attempted the open-air reliefs there after!

The whole composition is an illustration of total balance. It exudes the

Pallava grace, every square inch of it. Every character is perfectly

modelled. There is no overcrowding, no dramatisation. It is beauty in

simplicity. Worthy of contemplation, so savour the scene as best as you

can. I don’t want to say any thing more, it would speak for itself.

(Proverb)

On either side of the panel are two half-pillars (pilasters, if you are

too technical) on which is written 8 couplets, four on each side, in

Sanskrit in the Pallava Grantha script. I have mentioned before this

inscription is important. It is important for variety of reasons. First

it is a great poetry composed by the king himself. We may keep in mind

that Mahendra Pallava was an all-rounder. His political achievements are

legendary. He also initiated excavating cave temples in hard rock in

the south. He wrote two satirical plays, Mattavilasam and

Bhagavatajjukam. He was also a great painter/artist:

chitra-k-kaara-p-puli is one of his titles (self- given!).

The inscription caught the attention of the early epigraphists and the

meaning of the epigraph is debated even now. The first to translate was E

Hultzsch in 1890 and his reading is more or less followed even today by

most epigraphists. May his tribe increase! We should salute these

pioneers. But I am going to follow the interpretation of Miachael

Lockwood and his multi-disciplinary team from madras Christian College.

This is because their interpretation appeals to me. (You may wish to

follow Hultzsch if you desire. After all we live in a democracy.)

I propose to give a gist of the inscription first and then point out the

differences with the interpretation of Hultzsch. To help you to follow

the inscription at the site I am including the inscription, its

transliteration and translation.

Transliteration and translation of Mahendra Pallava’s inscriptional poem

The first sloka states that King Mahendra established a stone figure of

Siva in the cave temple of on the top of this hill in his own image, and

became ‘immortal’, like the God, on the earth.

The second stanza explains why Mahendra chose a hill. He says that he

chose the hill to justify Siva’s name as Girisa (mountain-dweller).

The third verse purports to explain the circumstances and the manner of

choice of this hill. Mahendra says that when proposed an earthly abode,

the God wondered how he can remain on the earth without seeing the

fertile country of the Chozhas and the river Kaveri. Then the king chose

the spot atop this Tiruchy hill facing the river.

The fourth describes how the temple became a reality. Here there is an

identification of God and the king.

The literary composition continues on the right pilaster. In this fifth

one the king is mischievous. Ganga, the daughter of Himavan, now fearing

that the Lord may become infatuated with the river Kaveri, let Her

mountain-dwelling to reside here along with the Lord. Here Lockwood et

al differ from the popular conception. Hultzsch read this stanza as

Parvati feeling worried came to reside with Her husband. I will talk

about this a little later.

The sixth verse says that he (Mahendra) himself has become embodied in

the image of Gangadhara. The whole poetry is supposed to be full of

double-meaning, more than one meaning. Sanskrit literature is famous for

this, called Dhvani.

The next verse says that the mountain was the crest-jewel of Mahendra’s Chozha province, this abode of Siva its chief jewel.

This last one is important. It says that through this stone-Siva, a

physical embodiment of Satyasandha (a title of Mahendra) was created,

and through this form, his fame was made eternal. By the way the

traditional understanding, that is, of Hultzsch and his followers,

differs from this.

Dhvani in Sculpture

I mentioned before that the poem and the sculpture are examples of

dhvani, an essential ingredient of Sanskrit poetry. Also mentioned was

that Mahendra was a great literary figure. His being a sakala-kala-

vallavan resulted in the dhvani being used in sculpture. And it is the

first time in history. His son contributes another first in his magnum

opus, in the Great Penance composition in Mahabalipuram, that is dvi-

samdhaana-kaavya (double-entendre poem, that is, a two-in-one poem). At

least some think so.

What is dhavani? Poetry may possess two levels of meaning: direct

meaning and a suggested meaning. This suggested meaning that appeals to

an aesthete is really the soul of poetry. This feature is called dhvani.

Thus the 8-stanza poem has both direct and suggested meanings. So the

sculpture too.

The poem directly refers to Siva as Gangadhara. The suggested meaning

could be Mahendra. Now let us look at closely. You may recall that

Mahendra specifically says that the Lord is made in his image. (What a

vain-glory!) So in the suggested meaning we may start with the hero

being the Pallava king himself. But what about the other characters in

the scene. Normally one finds a few divine characters, like Brahma,

Vishnu, Narada etc. In addition there would also be a few rishis and a

few bhoota-gaNa-s in attendance. In fact, the darbar of Siva has earned

the sobriquet Shambu-ki-barat (‘Shambu’s-friends-and-relatives-in-His-

wedding-entourage’) because of its motley composition! We have a gaNa,

four princely characters who can be taken for some divinities though

unidentified and two rishis in the background. We have an animal – we

couldn’t decide whether it is a bull or a dog – above Siva’s upper left

hand. A rishabha can be taken as appropriate, but if it is a dog, what

is a doing in this place? By the way dog is found in the Gangadhara

panel in another Pallava creation, the Kailasanatha Temple in

Kanchipuram, and again in the Kailasanatha Temple in Ellora, a

Rashtrakuta miracle. Various theories float around, and it looks these

are not convincing even to the floaters.

We shall then listen to Lockwood on the suggested meaning. The panel is a

celebration of Mahendra also. In the centre stands the Emperor

majestically. The four princely figures are the feudatories of the

Pallava-s. Two of the dynasties are represented here. The western Ganga,

identified by the namaste-ing Ganga seen on the left and the Kadamba-s

identified by the dog on the right. But how do you connect the Kadamba-s

with dog? It happened this way. Lockwood, while going through old

journals on Indian history, found that the Kadamba-s used dog-emblem in

their copper-plate grants”! While there is no doubt that Mahendra

Pallava was very creative, we now must accept that Lockwood is also very

imaginative!

Let me now point out the contributing factors to this double meaning.

The most important are the extraordinary and numerous titles of

Mahendra. I mentioned that he assumed more than 130 titles for himself.

Many of them are also the names of Lord Siva. The king skillfully weaves

these names into his poem to effect this double entendre. GuNabhara (I

and VI slokas), Purushottama (IV sloka) and Satya-sandhaa (VIII sloka).

Further he has skillfully employed words which could be understood in

more than one way. For example, the mountain itself may mean the

Himalayas or our own Tiruchy rock, it may be Parvati or Ganga by

daughter of mountain (gireendra-kanya) etc. To add to the poetic

alankaram words have been used adroitly. For example, sthanu is used in

two meanings, one to refer to the God himself and the other to mean

fixed, immortal, that this, the king has this become ‘immortal’.

The Pallava-s, as a dynasty, seemed to enjoy teasing. Many of the

Pallava monuments are puzzles. Some look to be intentionally made by the

Pallava-s themselves. There are so many, particularly connected with

the monuments in Mahabalipuram. Here the puzzle is: ‘Where is situated

the God mentioned in the poem?’

Lockwood’s new interpretation

Now let us look at two different solutions to the puzzle. As for as this

Gangadhara panel Hultzsch translated the word ‘nidhaaya’ as ‘placed’.

He also took gireendra-kanya to mean Parvati. So he, and the subsequent

people, looked for an anthropomorphic (sorry for art-ese, it simply

means ‘human-like’) idol of Siva and Parvati, naturally, in the

garbha-griham. To add to the confusion, there are two pits in the

garbha-griham. OK, one for Siva and the other, His consort. That fits

in. But what does not fit in is that Parvati image was not generally

installed in the sanctum. (Also, it is generally not a lingam that is

installed in the early Pallava sanctums. It could be a Somaskanda in

panel on its rear wall.) Hultzsch and the others did not consider that

the poem could refer to the Gangadhara panel, around which the poem is

engraved. This is in spite of the fact that the poem explicitly states

that the builder has made the God in his image. Another error of

judgment on the part of Hultazsch was, according to Lockwood,

understanding the expression ‘daughter of mountain’ as Parvati. Lastly,

Hultzsch misread (again according to Lockwood) another word. The word

was silaakshara in the 8th stanza. Hultzsch thought it is scribal error

and corrected it editorially as silaakhara, and translated as

‘stone-chisel’. But the word is bold and clear. Why did he do that? He

simply felt that this fits in with his interpretation.

Now our recent Poirot (all of you know this chap, the detective in the

Agatha Christi novels) cleared all these. Firstly, Lockwood translates

the word nidhaaya to mean ‘established’. Then he is of the view that by

‘daughter of the mountain’ the author refers to Ganga, and not Parvati.

Then was Ganga a daughter of Himavan? For this he points out that in

Ramayana, where the story of Bhagiratha is narrated Ganga is mentioned

as the eldest daughter of the King of Himalayas. Lastly, Lockwood

considers that there was no scribal error in silaakshareNa, and this

means ‘imperishable stone’, and then this meaning also fits in. And

there can be a few more interpretation. You may attempt. But, then you

will have to visit the shrine. Then my purpose is fulfilled.

You may ask me why I go into such a depth. If the matter is so important

to result in a number of research papers in reputed journals, and if

this is about one of our own monuments, shouldn’t we be aware of it? May

be we can also look at it our own way and come up with more innovative

theories.

|